By Cheryl Yau ’19

A key aspect of a liberal arts education that I really relish is the serendipitous exposure to ideas and people I would have not actively sought out on my own. In my very first semester at college, I registered for a class that I thought was titled “Violence, Media and Transnational Justice.” I later found out during the first class that I had misread the course title, and it was transitional justice, not transnational justice.

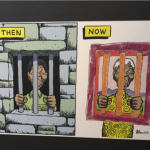

Transitional justice is a rapidly developing field that centers practices and processes targeted at helping individuals and societies deal with a legacy of past conflict and human rights abuses. It is both past- and future- oriented, for development is contextual and path-dependent. Due to the scale of the abuses, and the circumstances of transition, it is often a story of trade-offs: how do we balance justice, truth and peace? Are reconciliation and retribution mutually exclusive? There are a range of transitional justice tools that have been applied all around the world, the four pillars of which typically include truth-seeking, criminal justice, reparations and institutional reform.

While transitional justice practices may be most prevalent in Latin America and Africa currently, it is also personally relevant as we consider the history of the United States, the role of dark tourism (such as visiting former Holocaust concentration camps) and international celebrity activism. As an international student from Singapore, and, more broadly, Southeast Asia, I have also thought deeply about embedded coloniality in memory: whose stories do we remember? I wondered how many of my peers would know of Pol Pot’s regime in Cambodia, or of the killing fields in Indonesia, much less of U.S. complicity in these events.

Last summer, I was fortunate to be able to obtain funding from the European Union Center (based at Scripps College) to attend a summer school program on transitional justice and the politics of memory in Croatia. A major subfield of transitional justice is about dealing with and remembering the past, and there are few better places in the world to learn about memory politics than in the Balkans. The battle for the dominant narrative extended into street names and choice of language script, to the museums, sites of remembrances, the classroom, the newspapers and even to cemeteries. In my travels after the program, speaking to locals in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia (and being a participant of dark tourism at times) deeply impressed upon me the intractability of the conflict and its legacies on contemporary politics in a way that classroom learning would not have been able to match.

This semester, I am studying abroad at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. My choice of location was in part influenced by my interest in transitional justice and development—post-Apartheid South Africa has and continues to experiment with a slew of transitional justice mechanisms, the most well-known of which is the amnesty-based Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This has been shaping up to be a great decision—I see the switch in learning about to learning with my peers, I am better able to problematize the colonial dimensions of the field, and I am experiencing firsthand the relevance and emotional potency of the matter.

Since accidentally stumbling into the field (in a fairly embarrassing way), I have not looked back. This act of stumbling, and the dynamism involved, is one of my favorite things about the liberal arts model.